Best of 2015: The Redundant Gamer

by Mark R

First Published: Jan 9, 2015

Voted For By: Keegan, Lorna

Reason(s) For Vote:

“There’s a reason that I don’t watch much TV, and it’s not because I’m smart enough to work out the endings – because I’m really not. I love to feel engaged, and games provide that in a unique way, except when they don’t. I’ve never much liked the Telltale games, and Mark has informed me quite clearly of why, even if I hadn’t quite realised it myself. I loved reading this and seeing myself in the words, even if I’m not quite as into Borderlands as he is.” – Keegan

“A very well-written and reasoned piece that deals deftly with the issues surrounding games from devs such as Telltale. With many games now sharing the same field as Telltale’s, presenting choices and morality systems, the questions about what constitutes a game and what doesn’t and whether players actually do have any agency or whether it is all just a well-dressed illusion have never been more key. This article demonstrates and explores the problem in a great way, with a personal foundation.” ~ Lorna

I’ve always been fascinated by technology, even going back to the time I meticulously dissected my precious Stylophone to see how it worked and explore the possibilities of altering the sound it made, rather than the horrible wavering whine it produced by default. I was five years old at the time so, naturally, all my screwdriver did was to destroy it forever. It was one of my earliest technology-based memories, however, and probably what got me interested in electronic gadgets in the first place. By the time I was ten years old I was already storing information about my friends in a self-written piece of software which could only be accessed after a specific string had been input by the user. The level of security was, of course, hindered by the fact that you could simply press CTRL+C to issue a ‘break’ statement which, when followed by a list command, would then display every line of code, including the ‘secret’ data I had on my friends: their names, what colours they liked, names of pets, and… actually, that’s pretty much it.

I’ve always been fascinated by technology, even going back to the time I meticulously dissected my precious Stylophone to see how it worked and explore the possibilities of altering the sound it made, rather than the horrible wavering whine it produced by default. I was five years old at the time so, naturally, all my screwdriver did was to destroy it forever. It was one of my earliest technology-based memories, however, and probably what got me interested in electronic gadgets in the first place. By the time I was ten years old I was already storing information about my friends in a self-written piece of software which could only be accessed after a specific string had been input by the user. The level of security was, of course, hindered by the fact that you could simply press CTRL+C to issue a ‘break’ statement which, when followed by a list command, would then display every line of code, including the ‘secret’ data I had on my friends: their names, what colours they liked, names of pets, and… actually, that’s pretty much it.

Even though I’d while away the hours on Zorgon’s Revenge or Lone Raider, my deep interest in gaming didn’t really kick in until I started to spend time in the arcades. Somehow, the thrill of ending up with no money made the games a little more exciting, and having to place a reverse-charge call from a public telephone box to get someone to pick us up after we’d spent our bus fare home was the ultimate sign of a day well spent. Entering the arcade would always be the same; you’d see one guy hanging over Space Invaders, another glued to Defender, some poor sap plodding away at Frogger, and the smart folk were avoiding these cash guzzlers entirely to play snooker or pool and make their money last a little longer. We won’t talk about the young guys (myself included, a lot of the time) pouring coins into the fruit machines in the hope of eventually getting a pay out.

The point I’m trying to make is that it was like a bad sitcom. The same people would be there doing the same things every single day, and the outcome would never change, yet they’d continue to do it. The lack of variation was comforting in itself though, as you always knew what to expect and it probably amounted to the feeling that middle-aged men get when they walk into their local pub and it looks as though everyone is still there from the previous night. Nothing changed. Ever.

One day, however, everything did change. The aforementioned machines stood unattended, flashing away and blasting out their obnoxious theme tunes like an overlooked child screaming for attention. There was no clacking and clunking coming from the snooker or pool tables. The corner of the room which was normally an assault on the ears as dozens of coins dropped reluctantly into a metal tray below remained silent, and the colourful fruits spun no more. Something was amiss. If zombie apocalypses were as ubiquitous then as they are today, we would have sworn that we’d just ambled into ground zero, but then, out of the dead silence, came an ear-piercing scream of “Noooooooooo!”, followed immediately by a cacophony of disappointed yells and mumbles. And there, over in the corner, we saw it.

One day, however, everything did change. The aforementioned machines stood unattended, flashing away and blasting out their obnoxious theme tunes like an overlooked child screaming for attention. There was no clacking and clunking coming from the snooker or pool tables. The corner of the room which was normally an assault on the ears as dozens of coins dropped reluctantly into a metal tray below remained silent, and the colourful fruits spun no more. Something was amiss. If zombie apocalypses were as ubiquitous then as they are today, we would have sworn that we’d just ambled into ground zero, but then, out of the dead silence, came an ear-piercing scream of “Noooooooooo!”, followed immediately by a cacophony of disappointed yells and mumbles. And there, over in the corner, we saw it.

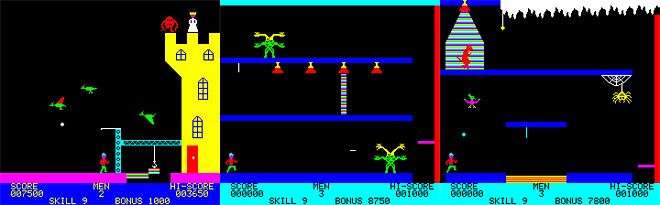

The entire population of the arcade was huddled around a single cabinet, where once stood a Formica-accented cigarette machine. As we hurriedly approached, I stopped dead in my tracks. I was already becoming a graphics whore, even though the best that the industry could offer at the time was slightly more detailed sprites than the year before, but there in front of me, only a few feet away, was the Defender kid slipping another 50p coin into what looked like a cartoon. An actual cartoon. It had smooth movement, realistic fire, a character with more detail and realism than any single person in the room had ever witnessed in a video game, and it was doing an incredible job of bankrupting a ten-year-old boy. This was Dragon’s Lair.

I couldn’t wait to get my grubby little hands on it, but the number of people who had already called dibs meant that it would be another week before that spectacular moment came. I got up earlier than I normally would on a Saturday, called upon my friends to see if they wanted to try out my cunning plan, and three of us headed into town to wait for the arcade to open. We were in first, armed with pockets full of 50p pieces that we’d borrowed from our respective parents’ gas-meter stashes. At only 10p per play, £3 would normally have lasted us hours on the machines we’d become familiar with, but with Dragon’s Lair it wasn’t long before my own well had run dry and I had to step aside to let one of the others try their luck with it.

Yet, as much as I yearned to play it, I walked away with a heavy heart. It was certainly impressive, graphically, and the tech behind it was quite overwhelming for its time, but there was absolutely no fulfilment from having played it. The gameplay was practically non-existent. Your character would simply go about his business and every ten or fifteen seconds you’d be given a ridiculously brief on-screen prompt to do something which would allow the story to continue. Miss your cue, or perform the wrong action, and your game was over. That was how brutal it was – an expensive memory exercise.

Yet, as much as I yearned to play it, I walked away with a heavy heart. It was certainly impressive, graphically, and the tech behind it was quite overwhelming for its time, but there was absolutely no fulfilment from having played it. The gameplay was practically non-existent. Your character would simply go about his business and every ten or fifteen seconds you’d be given a ridiculously brief on-screen prompt to do something which would allow the story to continue. Miss your cue, or perform the wrong action, and your game was over. That was how brutal it was – an expensive memory exercise.

The action may have been pretty frenetic, but with so many prompts coming in such a short space of time, it became obvious very quickly that this was designed specifically to extort as much money as possible from those who thought themselves up to the challenge. I wanted more from a video game than on-screen prompts and rapid respawns, along with an overwhelming feeling of redundancy, so my interest in Dragon’s Lair was short lived, and I vowed never to play another game like that in my life.

Then, just before this past Christmas, I was toying with the idea of starting GTA V as I’d been given it for my birthday. As with most of my evenings, the time quickly disappeared and I was approaching the point where it was probably too late to start something as in-depth as a GTA game, so I went out on a limb and treated myself to Tales From The Borderlands. It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of the Borderlands franchise, and spent more childhood hours in text adventures and point ‘n’ clicks than most kids these days have spent learning to spell, plus our man Ed had raved on endlessly about Telltale’s take on Pandora while we were at E3 last year, so I figured I had nothing to lose. I knew that it wouldn’t be the balls-to-the-wall action that I’d grown accustomed to, but I was prepared for that, and I fully expected to immerse myself in what would amount to being no more than endless QTEs, but if I could do it with Dragon’s Lair then I could easily do it with the folks over at Hyperion Corporation.

As someone who had never played a Telltale game before, I was surprised at just how little I had to do. This wasn’t like Dragon’s Lair where each scene would have prompts popping up so that I could progress to the next area, fighting skeletons and spindly octopus-type creatures with eyes on the end of the tentacles, or where the cues were so rapid that you could genuinely throw the term ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ around. This was like watching an endless cut scene which now and again asked you to select from a dialogue tree before continuing to play out.

As someone who had never played a Telltale game before, I was surprised at just how little I had to do. This wasn’t like Dragon’s Lair where each scene would have prompts popping up so that I could progress to the next area, fighting skeletons and spindly octopus-type creatures with eyes on the end of the tentacles, or where the cues were so rapid that you could genuinely throw the term ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ around. This was like watching an endless cut scene which now and again asked you to select from a dialogue tree before continuing to play out.

Even after making my choices, the reactions didn’t really sit properly, and so I started to experiment with my save files. When a conversation tree popped up I would try the first option and see where it took me, then I’d go back to my save point and try the other choices to mentally gauge the differences… yet there was absolutely no difference in outcome. At some points the same dialogue would play out regardless of the choice made, with perhaps one or two words changed to give the impression that my choice mattered.

To add insult to injury, even the action scenes required inconsequential input from me. Getting past a bandit at around ninety minutes into the story meant that I had to take him out, but no matter how I approached this particular aspect of the ‘game’, the outcome was identical every time – the bandit would be unconscious on the floor while my character stood over him with a stun rod in hand. There was a degree of choice within the action scene, don’t get me wrong, but it was merely Telltale Games throwing me a bone to convince me that I was instrumental in carrying the story forward whereas, in fact, I was 100% redundant. I played no part whatsoever, and felt like nothing more than a chump who had been cheated out of his cash by a company who fed me the line that I was playing an actual game.

Action: Jump on the bandit and attack him furiously

Action: Jump on the bandit and attack him furiously

Result: Bandit mocks you for not being able to take him down, and assumes you’re his friend, Eric

Action: Jump on the bandit and do absolutely nothing

Result: Bandit mocks you for not being able to take him down, and assumes you’re his friend, Eric

At this point, the bandit has a little tussle with you, knocks you off his back, and you both end up on the overhead gangway in a face/off situation with him holding on to your stun rod. He stares at it, wondering what it actually is. You now have another series of choices, with varying results:

Action: Offer to show the bandit what the stun rod is and, with it pointing at the bandit himself, activate the weapon.

Result: Bandit is blasted with an electric shock and thrown to the ground, sending the stun rod flying through the air.

Action: Say nothing at all and let the bandit fiddle around with the stun rod himself.

Result: Bandit sets off the stun gun which, as it’s pointed at himself, shocks him and throws him to the ground, sending the stun rod flying through the air.

At this point, you have another on-screen prompt where the stun rod is highlighted as it spins through the air in slow motion. If you catch it, you act like you’re a real swell guy and blurt out a James Bond-esque line of cocky arrogance, and if you miss it (or ignore it) then it’ll drop to the floor and you’ll pick it up again. No matter what you do in this ‘action’ situation, you’ll never be able to take out the bandit yourself; the bandit will always end up being stunned and thrown to the floor, and you’ll always end up with the stun rod in your possession again. The sixty-seven-second scene certainly does give the impression that you’re playing an important role, but the reality is that you could have done absolutely nothing and the outcome would have been exactly the same. Is that therefore gameplay? I don’t think so.

By the time you’ve sat through the two-hour-long episode (unless, of course, you prolonged the experience by switching back to your save file and testing various outcomes), you’re no more a part of the story than you would have been if you’d read a book. I understand that there are many games out there which aren’t actually games, in terms of the accepted definition, but they do still offer a degree of exploration and discovery where you’re free to make choices and go in your own direction. I understand that entirely.

By the time you’ve sat through the two-hour-long episode (unless, of course, you prolonged the experience by switching back to your save file and testing various outcomes), you’re no more a part of the story than you would have been if you’d read a book. I understand that there are many games out there which aren’t actually games, in terms of the accepted definition, but they do still offer a degree of exploration and discovery where you’re free to make choices and go in your own direction. I understand that entirely.

What I don’t understand, however, is how the first few moments of a game can feature the on-screen notification of “This game series adapts to the choices you make. The story is tailored by how you play.” when the reality is that you play no part in it whatsoever. Not only are all outcomes predetermined, but the process itself leaves the player redundant in almost all cases, and that’s false advertising as far as I’m concerned. Perhaps the choices made will affect the outcome of upcoming episodes, but ignoring everything I do in the first episode is not the way to keep a paying customer interested in your product. This isn’t 1983; the technology in a Telltale game isn’t groundbreaking enough to justify the non-existent gameplay like they did with Dragon’s Lair, and it’s insulting our intelligence to presume so.

Telltale had one chance to pull me in, and they blew it.

Last five articles by Mark R

- From Acorns to Fish

- Alone In The Dark

- Why Borderlands is Better Than Borderlands 2

- Falling Short

- The Division: A Guide to Surviving the Dark Zone Solo

There are no comments, yet.

Why don’t you be the first? Come on, you know you want to!