Antichamber – Review

by Adam B

|

One thing that most games have in common these days is the concept of the integrated tutorial, supposedly teaching you the controls and gameplay mechanics as you play, rather than requiring you to spend time up front learning them outside of the game proper. The problem with this system is that most games also utilise the “beat it into them with a blunt object” approach to teaching in a way that totally breaks immersion and makes it very clear that this is the bit where you Learn New Things™; “Commander Shepard, you are the galaxy’s last, best hope for salvation, now if you could just stand here for a few minutes while we show you how to Press Space To Run”. Antichamber, on the other hand, is continuously teaching you new things and, most of the time, you are blissfully unaware that it’s doing it until you find yourself applying the knowledge almost unconsciously.

One thing that most games have in common these days is the concept of the integrated tutorial, supposedly teaching you the controls and gameplay mechanics as you play, rather than requiring you to spend time up front learning them outside of the game proper. The problem with this system is that most games also utilise the “beat it into them with a blunt object” approach to teaching in a way that totally breaks immersion and makes it very clear that this is the bit where you Learn New Things™; “Commander Shepard, you are the galaxy’s last, best hope for salvation, now if you could just stand here for a few minutes while we show you how to Press Space To Run”. Antichamber, on the other hand, is continuously teaching you new things and, most of the time, you are blissfully unaware that it’s doing it until you find yourself applying the knowledge almost unconsciously.

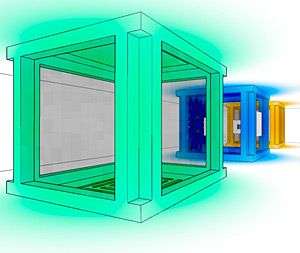

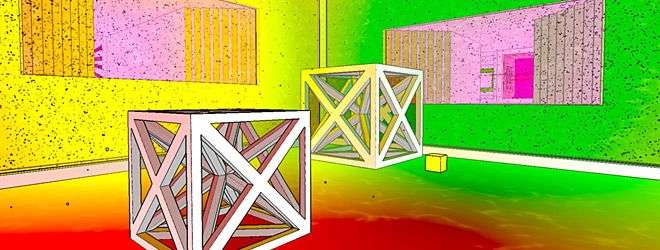

Antichamber is very much about subverting your expectations and it constantly plays with traditional level-design concepts; walls and floors appear and disappear as you move and turn, corridors wrap around on themselves, walking from one room into another and back again frequently leaves you somewhere other than where you started, and once something leaves of your field of view then anything could happen to it. It can take a little while to get used to working in a world that doesn’t adhere to the normal rules of geometry – I imagine it’s what getting lost in the TARDIS would be like – but after a while it stops being something that you’re consciously aware of and starts becoming a system you learn to work with. It’s something that’s very hard to describe without spoiling the experience, as many of the puzzles are knowledge-gated and even seemingly incidental information can substantially alter your understanding of the game world. You really just have to play it, it all makes far more sense when you can see it for yourself.

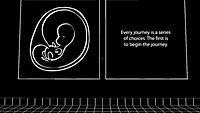

You begin your journey devoid of any context in a hub room, from which you can travel to and from any of the areas of the map that you have visited as well as change your control and graphics settings and review the various information panels that you have uncovered during your exploration. Your objective is simply to explore, to traverse the world by learning systems, solving puzzles and discovering previously hidden paths until you ultimately reach The End. A lot of the areas of the game are not directly linked or end in rooms that you cannot progress through, yet, or escape from, meaning that often your best choice is to return to the hub room and begin again from a different starting point. There are no voice-overs, no instructional text to speak of, no NPCs to interact with, no music and very limited ambient sound; there’s no story per se and while there are little panels of text dotted around the environment that can provide hints, state the obvious or simply pass commentary on life, they’re not really enough to be described as any kind of narrative.

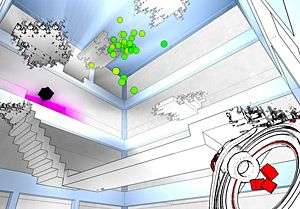

One of the most satisfying experiences in Antichamber is when you suddenly realise that the thing it’s been showing you at regular intervals isn’t just a fancy animation or extraneous visual flair, but is actual an important gameplay mechanic that you can use to solve a handful of previously “impossible” puzzles you’ve been staring blankly at for the last 20 minutes. On the flip side, one of the most depressing experiences is when you spend 20 minutes solving a puzzle using an incredibly complex series of steps that frustrated you no end, only to realise soon afterwards that there was an astonishingly simple solution staring you in the face that would have taken all of 30 seconds to implement.

One of the most satisfying experiences in Antichamber is when you suddenly realise that the thing it’s been showing you at regular intervals isn’t just a fancy animation or extraneous visual flair, but is actual an important gameplay mechanic that you can use to solve a handful of previously “impossible” puzzles you’ve been staring blankly at for the last 20 minutes. On the flip side, one of the most depressing experiences is when you spend 20 minutes solving a puzzle using an incredibly complex series of steps that frustrated you no end, only to realise soon afterwards that there was an astonishingly simple solution staring you in the face that would have taken all of 30 seconds to implement.

Almost nothing in the world is superfluous and if the game tells you not to look down then you probably shouldn’t look down, unless you want to see what happens when you do things you’re not supposed to, which of course you will; most of the time even failures are valuable learning experiences, you can’t die or trap yourself in inescapable situations so the only penalties for failure are your time and your pride. The visual style of the game is very simple – generally textureless, monochromatic corridors – so when you see images or colours you know they’re been put there for a reason, or at least to make you think that they’ve been put there for a reason.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In later parts of the game, when manipulating objects in the world becomes a more significant part of the puzzle mechanics, it can sometimes be a little frustrating trying position things accurately in three dimensional space. It’s not something that’s required too often and it’s hard to tell if it’s by design or a limitation of the controls, but from time to time it can lead to a little bit of shouting at the screen and repeatedly approaching the thing from various oblique angles in the hope of moving it where you want it to go. There is also currently a nasty crash bug that can occur when dealing with large cubes, something that the developer has said he’s trying to fix, but as far as I can tell none of the affected puzzles are required to complete the game and most of them are solvable in other ways, so it’s more an annoyance than anything game-breaking.

One of the downsides of basing the puzzles on learned mechanics is that by their very nature once you know how to solve them they tend to become trivial. There are very few sections of the game that require any kind of exact positioning, split-second timing or perfect coordination to traverse and you’re not really being timed, meaning that once you’ve completed the game, both in terms of reaching the end and solving all the non-essential puzzles, there’s very little reason to go back to it. This isn’t really a bad thing, the game is by no means short, a good six plus hours unless you’re a genius or a cheat, and there really are very few games that can match Antichamber in terms of a unique gameplay experience. One thing that has come of out my time with Antichamber is that I now really want to see a multi-player FPS with this kind of fluid geometry, however terrible it would probably be to play.

There, I made it all the way to the end of the review without mentioning Portal once…bollocks.

Pros- Unique

- Engaging

- Challenging

- Rewarding

- Very limited replay value

- Manipulating objects precisely can be a pain

Antichamber is a unique take on the first person puzzle genre; it never holds your hand but always shows you exactly what you need to know to progress, even if you don't realise it at the time. The puzzles can appear fiendishly difficult, but they're actually rather simple once you know how to solve them and rarely descend into frustration. It has a striking aesthetic and some exceptionally clever level design that often makes you feel like you're inside an Escher drawing. Its limited replayability is easily compensated for by the exceptional design, creativity and overall gameplay experience. If you like puzzle games, exploration or simply enjoy playing exceptional games, then you owe it to yourself to get Antichamber.

Last five articles by Adam B

- Deus Ex: Mankind Divided - Review

- No Man's Sky - Review

- The Curious Tale of The Consoles That Became PCs

- Quality of Life

- Why You Should Be Watching Dota 2 Right Now

There are no comments, yet.

Why don’t you be the first? Come on, you know you want to!