Always Sometimes Monsters – Review

by Edward

|

Choice can be difficult. Sometimes, everything you’ve ever known or will know will change irrevocably as a result of the decisions you make. On the other hand, there are also the choices you make where nothing will be fundamentally different, like the decision to have a ham sandwich or cheese and crackers instead. Then, there are the choices you make that feel like they’re yours to make, but they’re not, because you’ve been railroaded into a certain path.

Choice can be difficult. Sometimes, everything you’ve ever known or will know will change irrevocably as a result of the decisions you make. On the other hand, there are also the choices you make where nothing will be fundamentally different, like the decision to have a ham sandwich or cheese and crackers instead. Then, there are the choices you make that feel like they’re yours to make, but they’re not, because you’ve been railroaded into a certain path.

Always Sometimes Monsters is an indie narrative-driven experience created via RPG Maker, and you’d be forgiven for initially comparing it to the masterpiece To The Moon which, to date, still remains one of the most touching and emotional stories games have ever seen. However, while the latter is an incredibly linear (and seldom interactive) experience that’s more concerned about telling you a story than it is about you getting involved, Always Sometimes Monsters is keen on thrusting you right into the central role and encouraging you to see what its world has to offer. Unfortunately, because it focuses so much on the concept of choice, you’re always more than painfully aware the moment it won’t let you make your own.

The story begins when a hired goon tries to quit on his ruthless employer, only to end up in a Mexican stand-off with a vagrant, who tells the rest of the tale via flashback. Once the story is over, the mobster has to judge whether the storyteller is allowed to continue living or face the sweet embrace of death. The action continues at someone’s birthday party, where you then have to choose which of the twelve characters to have a drink with, with an equal split between male and female, and with ethnic diversities accounted for. Whomever you choose to join for a drink will then become the main character of the story, although this isn’t initially clear.

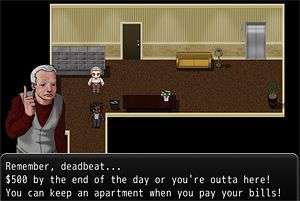

Once you’ve selected your main character you can then pick a love interest from a similarly diverse range of characters, which is more than willing to accommodate you if you want your characters to be in a gay, straight or lesbian relationship. It turns out that the party’s host has chosen to have a drink with your character because he wants to offer you a publishing deal, and after you shake on it, the action fast-forwards a year into the future, where you’re now a month behind on rent, and only have a day to cough up five-hundred dollars if you want to go back to your apartment. Problem is, you’re flat broke, so you’re going to need to find some cash, fast.

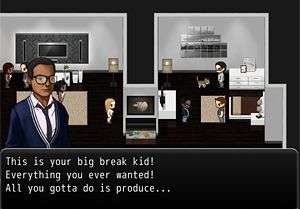

From here, you soon learn that your protagonist and their love interest have broken up in the year since the party, causing you to wallow in your own self-pity and fall behind on writing your great American novel, leaving you penniless, alone and in the bad books of nearly everyone who counted on you. It’s not long before you are handed two significant lifelines: your ex is getting married and has invited you to the wedding, prompting you to earn enough money to travel across the country to try and win them back before it’s too late, and your publisher wants the journal you plan to write on your quest, so he at least has something that he can salvage into a book.

From here, you soon learn that your protagonist and their love interest have broken up in the year since the party, causing you to wallow in your own self-pity and fall behind on writing your great American novel, leaving you penniless, alone and in the bad books of nearly everyone who counted on you. It’s not long before you are handed two significant lifelines: your ex is getting married and has invited you to the wedding, prompting you to earn enough money to travel across the country to try and win them back before it’s too late, and your publisher wants the journal you plan to write on your quest, so he at least has something that he can salvage into a book.

However, before you’ve even left the party, you will have probably smacked head-first into some of the game’s many irritations. For example, there’s no way to alter any of the in-game settings, be they movement speed, how quickly the dialogue text moves, the volume of the sound-effects and music, or the image resolution, forcing you to either have the action take place in a small, windowed view, or to put it on full-screen, with massive black borders taking up real estate on your monitor.

While trying to take screen-shots, I discovered that the button usually reserved for doing so instantly sends you back to the menu. Instead of having an image I could use, I instead had to start the scene from the beginning. I skipped through the dialogue, having already seen it, only to realise that it doesn’t make it clear when you’re about to be given a choice to make, so if you idly skip it then you’ll do what I did, which was accidentally say the wrong thing, meaning I had to go through the scene all over again. Then, when entering the names of my protagonist and their love interest, I made a mistake and discovered that there wasn’t an option to correct the name – at least, not one that was clear. So I had to restart the scene again. At this point, one of my friends wanted to try the game out, so we both resolved to play together with different combinations of characters – while taking alternative paths throughout the story – in order to see just how varied the end-experience becomes.

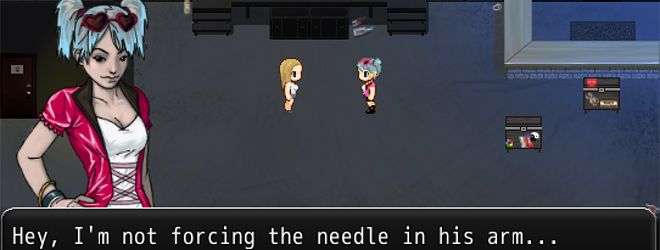

As you mingle among the party crowds and choose who’ll be involved in the story, you’ll undoubtedly notice the amount of effort that’s gone into how it all looks. Anyone who has more than a passing impact on the story has their own detailed portrait that accompanies their speech, and manages to mesh well with the otherwise retro aesthetic that permeates the rest of the experience. Everyone looks distinct in their own way, and each location has its own style that fits in perfectly with everything else.

Once you’ve allowed yourself to be taken in by the art style and set out to earn enough money to pay your rent, other problems come creaking to the fore. For one, your character moves at the pace of a geriatric snail and, try as I might, I never discovered a way to make them move faster. The layout of each location you visit throughout the story isn’t entirely clear, and you’ll often find yourself getting lost, or accidentally taking a wrong turn, which then takes ages to correct.

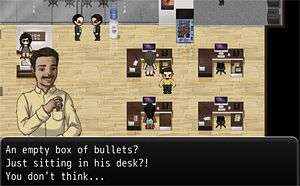

At least in the first town there’s a computer somewhere that shows you part of the map, but this opens up a whole can of worms in itself. You see, it’s located in the offices of Vagabond Dog – the creators of Always Sometimes Monsters – who’ve inserted themselves into the story, and who pop up in all of the coffee shops you may visit. Rather than their cameos being unrelated, their presence is fully Kaufman-esque, as they’re making the game you’re playing while you’re actually playing it. While it initially comes across as meta, it mostly ends up serving as an occasional immersion-breaker.

At least in the first town there’s a computer somewhere that shows you part of the map, but this opens up a whole can of worms in itself. You see, it’s located in the offices of Vagabond Dog – the creators of Always Sometimes Monsters – who’ve inserted themselves into the story, and who pop up in all of the coffee shops you may visit. Rather than their cameos being unrelated, their presence is fully Kaufman-esque, as they’re making the game you’re playing while you’re actually playing it. While it initially comes across as meta, it mostly ends up serving as an occasional immersion-breaker.

Worse still, they also make the incredibly smug and infuriating decision to point out flaws and problems with the game, then go on to do nothing else to address or fix it. Early on, they’re having a conversation about whether or not a tutorial is needed, because otherwise it’s not clear how you play or what the controls are. The answer is that a tutorial isn’t actually needed, because they can convey everything in metaphors. I don’t know about you, but I’ve yet to find a compelling enough metaphor to replace an instruction that tells you how to backspace if you type someone’s name incorrectly. The thing is, there’s no reason they couldn’t have had a tutorial, or at least given you the option to find out what the controls are outside of trial and error, because they can’t argue that it’d break the immersion because that would contradict the fact that they put themselves in their own sodding game.

There’s also the issue that it’s sometimes not very clear what you need to do next, or that you’ll only be told what to do once, so if you happen to forget what you’re meant to be doing at any point, or you don’t quite understand the instructions, then there’s no discernible method of finding out other than going everywhere on the map and hoping that you’ll luck into what you need to do.

At its core, Always Sometimes Monsters aims to be a deeper examination of the idea of morality and its portrayal in games. In the early stages, especially, it attempts to provide a greyer hue to a realm that normally only deals in black and white, but it doesn’t always bear out. The first main conflict is that there are ways to earn the money needed to pay your rent, but doing so may hurt people who don’t deserve it. However, in application, some of the choices you’re given are more cut and dry than they’re made out to be.

Do you tell your best friend that his music sounded better when he was messed up on heroin, or do you flush it down the drain so he doesn’t get addicted again? When your elderly neighbour gives you her bank card and asks you to buy her things, do you do as you’ve been asked or do you empty her bank account and leave her penniless and alone? You can be a morally-sound person and struggle to scrape together the money you need, or you can commit atrocious acts and gather the money lickity-split. Just because there’s no visible Mass Effect-like morality meter doesn’t mean that some choices aren’t just a case of goody-goody versus blatantly evil.

Do you tell your best friend that his music sounded better when he was messed up on heroin, or do you flush it down the drain so he doesn’t get addicted again? When your elderly neighbour gives you her bank card and asks you to buy her things, do you do as you’ve been asked or do you empty her bank account and leave her penniless and alone? You can be a morally-sound person and struggle to scrape together the money you need, or you can commit atrocious acts and gather the money lickity-split. Just because there’s no visible Mass Effect-like morality meter doesn’t mean that some choices aren’t just a case of goody-goody versus blatantly evil.

Even if you take alternative paths in multiple playthroughs, there are still fixed points in the story that players will have to deal with, regardless of how they’ve been playing. Whether you help your best friend out or ignore him, help him get clean or stick him on the smack, you’ll still have to deal with someone overdosing at the hospital, and the process of having to sort out their bills. If you take a temp job with the newspaper or the ad agency, you’ll still end up befriending the same person who’ll offer you a lift to the next town. It’s understandable, to an extent, but considering how open some of the choices are in the first town, it’s also unnecessary.

The brief stints of employment are also just the wrong side of tedious. When Shenmue was first released, the concept of having to do boring jobs to stay afloat was a novel idea that many appreciated, but here it’s just mind-numbingly boring. It’s a tricky thing to complain about, because there’s a deliberation that communicates that you’re supposed to find it a dull means to an end, but jobs tend to last far longer than they need to in order to make their point. At one point you could be made to shift boxes from a conveyor belt to the back of a truck, but you’re never told when you can finish. Your character will repeatedly comment on how long it’s taking and how little fun they’re having, but if you try and stop doing it then all the dialogue will hint that you’re meant to keep going and how quitting now would be lazy and the wrong thing to do.

Both my friend and I ended up doing the task for so long that the counter for how many boxes you’ve stacked broke, and yet we were still called out for quitting prematurely, despite it being the only way to progress through the story. Worse, no matter what you do in that situation, you’ll be confronted by someone later on who chews you out for even taking the job in the first place, but there’s no way of knowing that you didn’t have to take it.

Always Sometimes Monsters may feel very open in its earlier stages, but for the most part it’s actually an illusion. At best it’s a very mixed and confused experience, because it will think nothing of railroading you into a particular path and then subsequently criticising you for doing exactly what it told you to do. It will attempt to make you care for characters who feel like they’re going to be a bigger part of the story, only for you to never meet them again or for their presence to be nothing more than a cheap means of progression. You’ll start being given dilemmas that threaten to blur the lines, but then it’ll move on to another one that’s altogether more clear cut. Worse still, you’re often unable to see out the consequences of most of your decisions, so you’re less inclined to get invested later on.

It’s a game that heavily predicates itself on the impact of its story, but it’s one that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny and often leaves much to be desired. You’ll guess the most significant plot twists from a mile off, the initial presentation of the story absolutely cripples most of the potential opportunities for the multiple endings, and runs the risk of creating some ridiculous plot-holes or bizarre scenarios as a result. In fact, while one of the twists worked in my friend’s playthrough, it made absolutely no sense in mine because of the way that our respective flashback scenes played out.

It’s a game that heavily predicates itself on the impact of its story, but it’s one that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny and often leaves much to be desired. You’ll guess the most significant plot twists from a mile off, the initial presentation of the story absolutely cripples most of the potential opportunities for the multiple endings, and runs the risk of creating some ridiculous plot-holes or bizarre scenarios as a result. In fact, while one of the twists worked in my friend’s playthrough, it made absolutely no sense in mine because of the way that our respective flashback scenes played out.

Then there’s the matter of the endings. Always Sometimes Monsters boasts several of these, but it’s not really clear how some of them are affected by your actions throughout. Despite making some wildly different choices and decisions, both my friend and I ended up with exactly the same conclusion. After some wild experimentation, repeating the last hour again and again, I only managed to witness several darker sequences that end everything on an even more nihilistic note.

After about eight attempts we finally managed to stumble upon the ‘happy’ ending, but there was no clear way for us to discern how we achieved it, other than that it’s heavily based on the last thirty minutes, rather than your choices throughout. While that’s not necessarily a bad thing, it’s a massive discouragement to the idea of playing through another seven to nine hours again if you’re unsure that you’ll be rewarded with a more optimistic conclusion.

Overall, most of the story’s issues are also compounded by the fact that the game is rather wishy-washy on the importance of choice versus fate, so it’s never quite clear when certain underwhelming aspects of the story are deliberate or not. At first you’d be forgiven for thinking you understand what they’re trying to achieve but, as the tale continues, chances are you’ll find yourself confused by the inconsistent messaging, exacerbated by a morality system that presents dilemmas as two shades of grey when they couldn’t be more black and white. In addition, there are frequent glaring typos that mayke sum dierlogs hard to reed, and which occasionally change the meaning of entire lines.

Overall, most of the story’s issues are also compounded by the fact that the game is rather wishy-washy on the importance of choice versus fate, so it’s never quite clear when certain underwhelming aspects of the story are deliberate or not. At first you’d be forgiven for thinking you understand what they’re trying to achieve but, as the tale continues, chances are you’ll find yourself confused by the inconsistent messaging, exacerbated by a morality system that presents dilemmas as two shades of grey when they couldn’t be more black and white. In addition, there are frequent glaring typos that mayke sum dierlogs hard to reed, and which occasionally change the meaning of entire lines.

Unfortunately, Always Sometimes Monsters isn’t a title I can recommend. Every time it threatened to pull me in, it would do something to push me right back out again. Whenever it tried to immerse me, it’d immediately do something that jeopardised my enjoyment. It should be applauded for the amount of effort that went into its creation, and the way that it at least tried to create a compelling story filled with potential decisions. It’s just a shame that it didn’t all translate into something more memorable and incredible.

Pros- It has a great visual style

- A refreshingly diverse cast to choose from, with the ability to play as a straight, gay or lesbian character

- There's a distinct effort to give the player a wide variety of choices and decisions, as well as different approaches of play, even if not all of them entirely work

- There's a great Barenaked Ladies reference at one point

- The music is often irritating and quickly becomes repetitive

- Spends so much time crafting the illusion of choice, only to frequently railroad your choices and criticise you for doing what you're told

- Progression occasionally comes down to luck or precognition, rather than skill or merit

- Controls aren't explained, there's no apparent way to walk any faster than zero miles an hour, and the button normally reserved for screen-shots resets the game

- The creators have a cameo that only serves to point out flaws they could easily have fixed, while undermining the game's reality

- An underwhelming take on morality in games that's frequently undermined by a script full of issues, inconsistent messages and typos

- Not quite enough diversity of choice after the first location to warrant another playthrough

At first glance, Always Sometimes Monsters looks to have plenty of potential. However, the deeper you delve, the more its myriad issues become apparent. While some could be forgiven if the script and the story were up to scratch, both are flawed enough that they fail to make up for shortcomings elsewhere. While this could have been an incredible take on morality and choice in games, it ends up falling short of its goals, and will probably leave you more enraged than enlightened, if not just bored and disappointed. Although there's Always Sometimes potential there, it's an Always Sometimes missed opportunity.

Last five articles by Edward

- Best of 2015: Journey's End: A New Beginning

- Journey's End: A New Beginning

- You Can't Choose Your Happy Ending

- Okay, Let's Fix Comedy In Games - The V-Effekt

- Time Keeps On Smashing Away

There are no comments, yet.

Why don’t you be the first? Come on, you know you want to!