Broken Age – Act One Review

by Edward

|

It’s odd to think that Kickstarter is something that’s taken for granted these days. In its short inception, the crowd-funding service has gone from “next big thing” to “cynically exploited” to “obligatory dumping ground for projects publishers are umming and ahhing about”. If you’re one of those people who like to appropriate blame, then it could conceivably be laid squarely at the feet of Double Fine.

It’s odd to think that Kickstarter is something that’s taken for granted these days. In its short inception, the crowd-funding service has gone from “next big thing” to “cynically exploited” to “obligatory dumping ground for projects publishers are umming and ahhing about”. If you’re one of those people who like to appropriate blame, then it could conceivably be laid squarely at the feet of Double Fine.

Run by Tim Schafer – creator of Full Throttle, Psychonauts and other critically-acclaimed games you’ve statistically never played – the company helped Kickstarter explode onto the mainstream thanks to the (some would call in)famous campaign that saw the company ask for four-hundred thousand dollars so they could make a point-and-click adventure game just like they were in your childhood.

Nostalgia is a powerful tool and, instead of meekly hitting their target, The Double Fine Adventure campaign raised nearly three million dollars more than they initially asked for, and that’s arguably when trouble began. The massively extended budget meant that the scope became bigger to justify the amount of investment until they’d almost ran out of backer money, prompting them to split the final product into two acts and release it on Steam via Season Pass – with the second part arriving sometime in the future – in the hopes that they could recuperate their budget that way.

Now, fifteen months after its originally scheduled release, and long after it helped sour many on the concept of Kickstarter-backed projects, it’s finally been released. It may not be the salvation of the genre many would expect it to be, but it’s a fine return to form for Schafer and co.

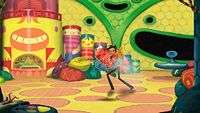

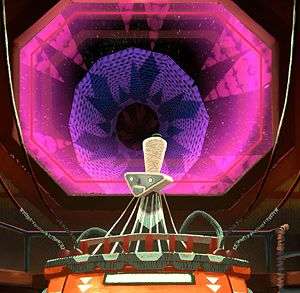

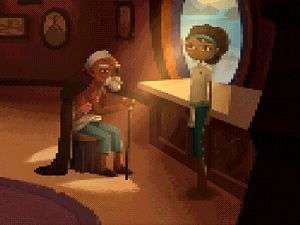

In essence, Broken Age tells the story of two teenagers who are attempting to lead a life separate from the one that their parents have chosen for them. Players can choose whether to initially play as Vella – a maiden-slash-wannabe-monster-slayer with a grudge against tradition and a penchant for staying alive – or Shay, a mollycoddled captain who dreams of some real adventure, or at least something that involves him taking on fewer ice-cream avalanches.

You can tackle both stories in any order you’d like, with the ability to swap between either side available whenever you take a peek at your inventory. There’s no “right” order to do things, but I found myself tackling Vella’s half in its entirety before moving on to the other. That being said, it did feel like you should at least try the opening part of Shay’s chapter before anything else as, while neither tutorialises, the start of his journey felt like a natural fit for one. Shay’s intentionally and hilariously patronising opening moments make perfect sense within thematic context, but I can’t help but admit it was at least slightly odd climbing Vella’s difficulty curve only to start again from the bottom once I’d moved on to the second half. Admittedly, I don’t think that Broken Age needed a tutorial, but it could have benefited by clearly explaining its intent and the presence of the mechanics of puzzling, rather than the puzzles themselves.

You can tackle both stories in any order you’d like, with the ability to swap between either side available whenever you take a peek at your inventory. There’s no “right” order to do things, but I found myself tackling Vella’s half in its entirety before moving on to the other. That being said, it did feel like you should at least try the opening part of Shay’s chapter before anything else as, while neither tutorialises, the start of his journey felt like a natural fit for one. Shay’s intentionally and hilariously patronising opening moments make perfect sense within thematic context, but I can’t help but admit it was at least slightly odd climbing Vella’s difficulty curve only to start again from the bottom once I’d moved on to the second half. Admittedly, I don’t think that Broken Age needed a tutorial, but it could have benefited by clearly explaining its intent and the presence of the mechanics of puzzling, rather than the puzzles themselves.

For example, one obstacle in Vella’s path requires you to combine items in your possession in order to proceed; it may be an established trope in point-and-clicks but there’s no prior indication that you can do this and from my recollection this type of solution never crops up again. Objects in your inventory also need to be dragged and dropped to their intended targets, as simply clicking on them will result in a quip about their description, but this is never explained and is something the player has to figure out for themselves.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The art of playing a point-and-click used to be innate back in the old days because the presentation was often simple or at least made it clear how it was played, but at times the standard mechanics in Broken Age have been streamlined in a way that has the unintentional consequence of making them feel muddied. It’s almost as though Double Fine have seen fit to “revive” the genre on their own terms rather than anyone else’s.

At times it seems like Schafer and Co haven’t actually paid attention to the advancements that have been made in their absence, but instead focused on problems that used to exist when adventuring was still in vogue during the nineties, and ignored what everyone else has been doing. The ability to skip dialogue is present, but it cuts out the entire conversation thread rather than just one line and is assigned to the space-bar, rather than the left-click command as is the case everywhere else. There’s the option to double-click to move from one scene to another, but it often takes longer than it should because the camera will be zoomed in in such a way that you have to move halfway across the area before it draws back enough that you can activate the command.

At times it seems like Schafer and Co haven’t actually paid attention to the advancements that have been made in their absence, but instead focused on problems that used to exist when adventuring was still in vogue during the nineties, and ignored what everyone else has been doing. The ability to skip dialogue is present, but it cuts out the entire conversation thread rather than just one line and is assigned to the space-bar, rather than the left-click command as is the case everywhere else. There’s the option to double-click to move from one scene to another, but it often takes longer than it should because the camera will be zoomed in in such a way that you have to move halfway across the area before it draws back enough that you can activate the command.

Pixel-hunting is a thing of the past and everything you can click on is clearly highlighted by the cursor, but there’s no ‘reveal-hot-spot’ command – something that’s essentially standard in this genre by now. Broken Age fixes some of the mistakes of the past, yet it really should have paid attention to the solutions of the present when doing so, because if it had then it could have been pioneering instead of playing catch-up.

It works heavily in its favour that Broken Age is charming, often hilarious and frequently intelligent, then. The bulk of this comes down to the writing, which feels just as much considered as it does silly and banal. There’s a greater maturity and cohesion to both the story and a vast sense of the humour, and although there’s nothing as iconic or infinitely quotable as three-headed monkeys or insult sword-fighting, there’s still plenty to laugh and smile at.

In the early stages of Vella’s journey, the humour is less laugh-out-loud than it is utilised to juxtapose the saccharine world and the quirkiness of the people that inhabit it against the horrifying reality of the Maiden’s Feast – a ceremony in which teenage girls are willingly sacrificed to an eldritch monstrosity – and the shocking complacency and exuberance with which it’s regarded. From there the jokes tend to focus more on the various characters she meets, from almost-certainly a cult leader Harm’ny Lightbeard to Curtis, a lumberjack who has become deathly afraid of the trees since they’ve started screaming at him.

In the early stages of Vella’s journey, the humour is less laugh-out-loud than it is utilised to juxtapose the saccharine world and the quirkiness of the people that inhabit it against the horrifying reality of the Maiden’s Feast – a ceremony in which teenage girls are willingly sacrificed to an eldritch monstrosity – and the shocking complacency and exuberance with which it’s regarded. From there the jokes tend to focus more on the various characters she meets, from almost-certainly a cult leader Harm’ny Lightbeard to Curtis, a lumberjack who has become deathly afraid of the trees since they’ve started screaming at him.

The style of comedy feels much different to Shay’s chapter as the humour feels more understated in Vella’s, with hilarious moments serving as the payoff to your actions rather than the normal state of play. Shay’s story is much the opposite, with the jokes coming thick and fast and more serious and poignant events acting as significant story beats. By the end of the first act there’s plenty of different types of humour to satiate you and, unless you lost your sense of humour in a terrible accident, it’s unlikely that you’ll have failed to find something to laugh at.

That humour, charm, and writing is all bolstered by the generally superb voice-acting, with several celebrity cameos filling up the roster and causing a fair few utterances of “is that who I think it is?”. Main character Shay is voiced by ring-destroying Elijah Wood, Adventure Time creator Pendleton Ward fills a brief blink-and-you’ll-miss-it role, and the aforementioned Harm’ny and Curtis are voiced by perpetual man-child Jack Black and “in Big Bang Theory sometimes” man Wil Wheaton respectively.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The cast highlights are undoubtedly Elijah Wood and Jennifer Hale, who plays his ship’s computer, and despite their relatively large set of lines there’s never a foot put wrong. Everything is delivered expertly and perfectly matches the tone and context of what’s going on. The same can’t be said of Masasa Moyo’s turn as Vella though, as her delivery and tone will often feel flat and ill-fitting with the action on-screen. It’s not a terribly good performance, which can be a bit of a disappointment when her airy, devil-may-care monotone accompanies you for half of the running time.

That being said, it was at least rather refreshing to have a female lead to play as, and I did enjoy the fact that there were more female characters than male, as well as the fact that they had more than a few lines of dialogue and were – for the most part – actually remotely fleshed out, rather than vacuous plot devices.

Similarly, the puzzles on display offer a bit more depth than you’d initially expect and feel quite considered, given that solutions in Schafer’s prime would skew more towards the banal than logical at times. If you’re adept at the genre then you’re not going to get stuck very often and, thanks to the fact that every interactive object in an environment prominently stands out, you won’t miss the lack of the ‘reveal-hot-spot’ command as much as you think you would. Admittedly, while I found myself stumped on a fair few occasions, I never felt like the answers stumbled into the dreaded realm of developer’s logic – solutions that only make sense through a garbled line of reasoning that only the person writing it could conjure. One or two puzzles came close to garnering that sentiment, but that label would soon disappear when you actually thought about the solution; they would make much more sense in retrospect, rather than leaving you wondering how that conclusion could ever be reached.

Similarly, the puzzles on display offer a bit more depth than you’d initially expect and feel quite considered, given that solutions in Schafer’s prime would skew more towards the banal than logical at times. If you’re adept at the genre then you’re not going to get stuck very often and, thanks to the fact that every interactive object in an environment prominently stands out, you won’t miss the lack of the ‘reveal-hot-spot’ command as much as you think you would. Admittedly, while I found myself stumped on a fair few occasions, I never felt like the answers stumbled into the dreaded realm of developer’s logic – solutions that only make sense through a garbled line of reasoning that only the person writing it could conjure. One or two puzzles came close to garnering that sentiment, but that label would soon disappear when you actually thought about the solution; they would make much more sense in retrospect, rather than leaving you wondering how that conclusion could ever be reached.

However, the fact that this is the first act of two is the most evident here, as the difficulty curve starts to plateau before the end of each character’s respective side of the story. It’s great that there’s nothing particularly cruel or nasty waiting in the wings just because the events close on a cliffhanger, but you’ll be forgiven for craving just a little but more. Depending on the method and order you choose to tackle both sides of the story, there’s also the risk that the challenge will form more of a difficulty wave – rising, climaxing, then dropping back to zero only to start all over again. It’s a necessary risk in granting the players total freedom in how they wish to progress, but a risk nonetheless.

Far less of a risky proposition is the art style, which manages to look breathtakingly stunning in nearly every single frame. It effortlessly provides a unique aesthetic that you’d be hard-pressed to find elsewhere while retaining that undeniable trademark of a Schafer and Double Fine product. Every screen-shot is filled to the brim with intricate detail, and it really helps the world come alive in a way that you’d never have initially imagined. The amount of effort that’s gone into making Broken Age this beautiful must have been immense, and it’s hard not to talk about it without getting carried away at times. If Double Fine start making point-and-clicks on a more regular basis then Daedalic’s art department should be prepared to jump every time they look over their shoulders.

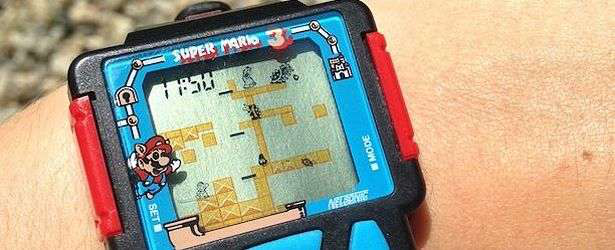

Less noteworthy is the soundtrack, which has that unfortunate distinction of perfectly complementing the events on-screen, but is instantly forgotten as soon as you’ve exited to the desktop. I never found myself turning the music off or consciously ignoring it, but I couldn’t recall any of the tracks if I tried. Also forgettable is a secret command hidden in the options that turns the art style into a fuzzy collection of pixels at the press of a button. It’s a nice touch, but while it worked in the Monkey Island special editions for those who wanted to compare the art of new with the pixels of old, there’s no nostalgia to give you a driving compulsion to see what every screen would look like if you were trying really hard to make it look retro.

Less noteworthy is the soundtrack, which has that unfortunate distinction of perfectly complementing the events on-screen, but is instantly forgotten as soon as you’ve exited to the desktop. I never found myself turning the music off or consciously ignoring it, but I couldn’t recall any of the tracks if I tried. Also forgettable is a secret command hidden in the options that turns the art style into a fuzzy collection of pixels at the press of a button. It’s a nice touch, but while it worked in the Monkey Island special editions for those who wanted to compare the art of new with the pixels of old, there’s no nostalgia to give you a driving compulsion to see what every screen would look like if you were trying really hard to make it look retro.

I clocked in a little over four hours with the first act of Broken Age – a fairly decent amount considering other, non-fragmented titles of its ilk routinely last around eight or nine, but possibly less so when you consider the budget attached. I’ll admit that I never once found myself thinking about how much it garnered in Kickstarter pledges while I was playing it, and even after finishing it my mind didn’t immediately ponder the question of whether it felt like three million dollars’ worth of game – or half of that, considering it’s the first of two parts.

If you’re willing to ignore its Kickstarter funding – or simply don’t care – then Broken Age is an appealing proposition. It’s a cautious-but-optimistic return to form for Tim Schafer in a genre he helped initially bring into the mainstream, but it’s one that could have benefited from the acknowledgement that adventure games didn’t stop when he did. Some of the mechanics aren’t as strong as they could have been if attention had been paid to the work companies like Daedalic and Telltale have been pitching in while Schafer was gallivanting overseas, while attempting to tell two coinciding stories can make the challenge feel imbalanced depending on the way you choose to play it. It might not be possible to see the whole picture yet, but Broken Age could be the start of something truly memorable.

Pros- Breathtaking art style filled to its pores with lavish detail.

- Mature, considered storytelling that isn't just trying too hard to be overly silly or poignant.

- A wide variety of jokes that ensure that there's plenty to laugh at.

- Vella and Shay's chapters feel suitably distinct and unique.

- Some challenging puzzles that don't err on the side of Developer Logic.

- While the mechanics aren't perfect, it's at least evident that Schafer's made a concerted effort to learn from the flaws of his past titles.

- Amazing voice-acting from all but one member of the cast, with the celebrity cameos acting a surprise highlight.

- Unfortunately, that only bad voice-acting performance is the female lead you have to spend half the game with.

- Entirely forgettable soundtrack, even if it expertly accompanies the action.

- Four hours for the first half might feel a little short to some.

- Can feel like an inconsistent difficulty curve depending on how you tackle both sides of the story.

- Mechanics feel like they're trying to fix the problems of the nineties without paying attention to the solutions of the present.

- It's not entirely clear yet if it's worth the budget given to it by Kickstarter backers.

Considering its well-documented and - to some - contentious Kickstarter campaign, there's no easy way of summarising Broken Age. It's easy enough to disregard its considerable backing and budget while you're actually playing it, but there's no way to provide a definitive statement while the second half is yet to play out.

Each side of the story is consistent and cohesive in its own right, but feel slightly inconsistent when presented as a whole. It's not particularly innovative, but it appropriates the trappings of the genre well, minus some well-needed features that should honestly be standard by now. There are definitely flaws, some of which should arguably have never been there, but when everything aligns - and it frequently does - you'll soon forget all about them and find yourself enjoying the ride more often than not.

For now though, Broken Age has some great moments, some brilliant laughs and a far more mature story than you'd expect from one of the zaniest minds the industry has to offer. It's unlikely that a minute will go by without a smile on your face, and although it's yet to have a moment that can truly be called iconic it's a considerably impressive return to form for a man who hasn't dabbled in the genre for nearly twenty years, and it's well worth your time as a result.

Last five articles by Edward

- Best of 2015: Journey's End: A New Beginning

- Journey's End: A New Beginning

- You Can't Choose Your Happy Ending

- Okay, Let's Fix Comedy In Games - The V-Effekt

- Time Keeps On Smashing Away

There are no comments, yet.

Why don’t you be the first? Come on, you know you want to!