The Cave – Interview With Ron Gilbert

by Edward

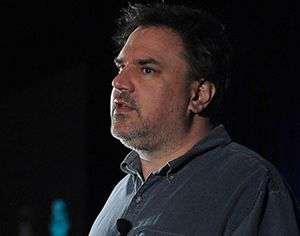

They say you should never meet your heroes; the expectation you build up of them in your head versus the reality is often disillusioning and, at worst, heartbreaking. With this in mind, I was incredibly nervous when the chance came to meet Ron Gilbert, creator of Deathspank, Maniac Mansion and Putt-Putt. In front of me was the man responsible for the first two Monkey Island releases – titles so influential to me that they shaped my entire personality, sense of humour and obsession with storytelling. Nintendo may have pushed me into gaming, but the adventures of Guybrush Threepwood sparked my life-long love affair, and I finally got the chance to talk to the man who, for all intents and purposes, is the reason why I spend my life writing about games.

They say you should never meet your heroes; the expectation you build up of them in your head versus the reality is often disillusioning and, at worst, heartbreaking. With this in mind, I was incredibly nervous when the chance came to meet Ron Gilbert, creator of Deathspank, Maniac Mansion and Putt-Putt. In front of me was the man responsible for the first two Monkey Island releases – titles so influential to me that they shaped my entire personality, sense of humour and obsession with storytelling. Nintendo may have pushed me into gaming, but the adventures of Guybrush Threepwood sparked my life-long love affair, and I finally got the chance to talk to the man who, for all intents and purposes, is the reason why I spend my life writing about games.

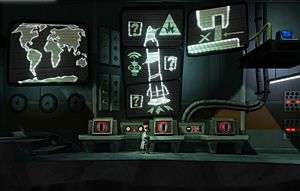

Gilbert’s latest title, The Cave, isn’t your typical adventure game; players choose three of seven characters to traverse a mysterious sentient Cave that chooses to address those controlling the characters rather than the protagonists themselves. Your potential squad consists of a scientist, a hillbilly, twin orphans, a knight, a monk, an explorer, and – my personal favourite – a time-traveller, all of whom wish to learn something about themselves by visiting said Cave, whilst also seeking to keep their darkest secret hidden. Single players can hot-swap between each of their three heroes, but it’s also possible for up to three people to play together. “It’s a lot of fun to watch three people playing at once,” Ron explained, “Actually, three people get through the game a lot faster, because there’s three brains. It’s a lot of fun because it’s kind of like bees shooting through as they run through the world.”

Though there’s nothing stopping you from completing The Cave all by yourself, I did find myself having a lot more fun when playing through the demo with fellow writer Keegan on a previous occasion. Puzzle-solving is a less painful affair when there’s an alternative perspective on the situation, and it even became a competitive affair as I subconsciously found myself trying to think of the solution before him and trying to take all the credit. The team approach to overcoming the obstacles adds a well-needed evolution to the adventure genre, and it could be one that helps get people who aren’t traditionally gamers to get in on the action as well.

Though there’s nothing stopping you from completing The Cave all by yourself, I did find myself having a lot more fun when playing through the demo with fellow writer Keegan on a previous occasion. Puzzle-solving is a less painful affair when there’s an alternative perspective on the situation, and it even became a competitive affair as I subconsciously found myself trying to think of the solution before him and trying to take all the credit. The team approach to overcoming the obstacles adds a well-needed evolution to the adventure genre, and it could be one that helps get people who aren’t traditionally gamers to get in on the action as well.

“When we did the co-op stuff, one of the things I’ve always thought is that in each household there’s usually one predominant gamer, and then there’s other people who are not really gamers, but maybe they like to sit on the couch and watch the other person play, but if they could just pick up a controller then they don’t really have to do anything except follow the other person around. If they then think of something to do, then they can do it, and they can switch characters any time they want. It’s not that he’s the scientist and she’s the hillbilly, although you sometimes get that dynamic of the older and younger brother and there’s a lot of fighting. There’s a lot of “stop taking the hillbilly from me!”, I can imagine a lot of kids are going to get sent to their rooms after playing The Cave“.

Though the early sections had small platforming sections (that would amusingly cause The Cave to call you out if you kept jumping into the spike pits nearby), Ron assured us that you wouldn’t have to rely on pixel-precision in the title’s later stages: “I hate platformers, that’s why there are no puzzles in The Cave that involve getting your timing right or mastering tricky jumps.”

The Cave isn’t without references to the glory days of adventure games: a vending machine early on advertises New Grog – a throwback to Ron’s most iconic series and one that he’s keen to return to, but may not get the chance to do after Disney’s recent acquisition of Lucasarts. “If I could get the rights back to Monkey Island, I think it’d be really fun to go back there“.

Those who paid attention to Telltale before they exploded into the mainstream with their take on The Walking Dead will know that they recently turned their hand to the pirate franchise – a season of episodic titles that credits Gilbert as the ‘Visiting Professor of Monkeyology’. “I thought they were good; I wasn’t a big fan of the episodicness, I felt they would have been stronger if it was all one game, but I thought they were really good. They only ever licensed Monkey Island for one season, and Lucasarts were kind of a pain to work with a little bit for them, and now they’re doing The Walking Dead.”

Those who paid attention to Telltale before they exploded into the mainstream with their take on The Walking Dead will know that they recently turned their hand to the pirate franchise – a season of episodic titles that credits Gilbert as the ‘Visiting Professor of Monkeyology’. “I thought they were good; I wasn’t a big fan of the episodicness, I felt they would have been stronger if it was all one game, but I thought they were really good. They only ever licensed Monkey Island for one season, and Lucasarts were kind of a pain to work with a little bit for them, and now they’re doing The Walking Dead.”

Telltale weren’t the only ones to find Lucasarts difficult to work with in recent years, as discovered when Ron explained his issues with the company: “Lucasarts are really schizophrenic; every three or four years they would phone me up and say “Ooo, we really want to do another Monkey Island, can you make another Monkey Island?”, and I’d be like “yeah, that’d be a lot of fun“, and then I’d go there and I’d talk to them and then they’d fire their president. The next president never contacts me about Monkey Island, I guess they kind of figured that the last guy got fired cos he called me and asked for another Monkey Island. Then he gets fired and the next one calls me up wanting to make another Monkey Island. They got addicted to the Star Wars drug; it made them so much money that they thought “why bother making other games when we can just make more Star Wars games?””

Long after the days of Lucasarts, Ron now works at Double Fine – creators of cult hits Psychonauts and Brutal Legend – alongside Tim Schafer, whom Ron worked with on the first two Monkey Island releases. “The only difference now is that back at Lucasfilm I was his boss, so I’d get to boss him around, but I can’t do that any more. I try to boss him around, but he doesn’t listen to me any more.”

Long after the days of Lucasarts, Ron now works at Double Fine – creators of cult hits Psychonauts and Brutal Legend – alongside Tim Schafer, whom Ron worked with on the first two Monkey Island releases. “The only difference now is that back at Lucasfilm I was his boss, so I’d get to boss him around, but I can’t do that any more. I try to boss him around, but he doesn’t listen to me any more.”

Soon came the moment I was waiting for – the opportunity to talk to Ron one-on-one about The Cave, writing for videogames, the difficulty of creating comedy and how everything changes from conception to completion.

The Cave is similar to Maniac Mansion in the sense you can choose between several characters and events play out differently as a result, was that previous experience instrumental in helping everything come together?

Yeah, definitely; I always liked the seven characters in Maniac Mansion, but when Gary and I were making Maniac Mansion, it was the first adventure game that either of us had designed, and it was kind of an afterthought. I mean, there’s a whole lot of charm and I love that game to death, but I really wanted to re-look at seven characters and really make the stories for the seven characters a lot more meaningful, along with whatever skill they had, but yeah, it was very heavily influenced by Maniac Mansion.

How difficult was it to balance each section of the game in a way that it had to be possible with any character combination in terms of puzzle design?

That was one of the hardest things that we had to do, because we had to make sure the game was playable from beginning to the end, but we also wanted to make sure the game was actually different when you play it. When you play it with the Time-Traveller she can teleport through boards and stuff, so you might play with her and teleport through a door, grab something you need and teleport out, but when you play it again without her, you run along and you get to that door and you’re like “Oh, I don’t have the Time-Traveller” and now there’s a bunch of puzzles you have to solve to get the door open. That’s kind of how we deal with all the multiple solutions of things, because characters can jump around certain puzzles if they use their abilities.

The puzzles I played in The Cave were more immediate and short term than say, Monkey Island, where items you picked up would become useful much later on. How has your philosophy of designing puzzles changed over the years?

What you’re playing here is what we’re calling the “Intro Area”, so we have kept the puzzles a little bit simpler, because we figure there’s probably a lot of people who will play this who have not played adventure games before, so we’ve kept things a little bit simpler and a little bit more immediate to keep stuff in peoples’ minds. As you play more The Cave does open up quite a bit and there are going to be much larger areas where you’re wandering around; there’s this whole underground Carnival area you come to, which is quite a large area, so there’s a whole lot of puzzles as you’re going around the Carnival and trying to win the different Carnival games and that kind of stuff, so the game does open up after this area.

The narrative twist in this title is that the Cave itself is narrating and talking directly to the player, rather than the characters, as they explore. Was this always your intention, or were the storytelling aspects originally quite different? Will The Cave have its own agenda for guiding the player, too?

The narrative twist in this title is that the Cave itself is narrating and talking directly to the player, rather than the characters, as they explore. Was this always your intention, or were the storytelling aspects originally quite different? Will The Cave have its own agenda for guiding the player, too?

That was always my intention; one of the main things about the idea was always that we have this sentient talking Cave communicating with the player. As for the agenda, you’ll going to have to play the game and find out.

In the story the Cave is a place people go to to learn something about themselves and who they might become, and they all have a dark secret hidden away inside them. It’s a slightly more ominous tone than your previous titles, how did you maintain the level of humour veterans of your games may come to expect?

Whenever you’re doing something where there’s – or at least when I’m doing something – where there’s a more serious, darker side, I think doing comedy around it makes it a little more palatable. Like the Twins, they do some really bad things in the game, but they kind of make fun of it in a way – the Cave kind of makes fun of fun of it in a way – that kind of makes it okay that they’re poisoning their parents, you know? I’ve always threatened to do stuff that’s a little bit serious; if you really strip away everything in Monkey Island, it’s a serious story, but you just kind of build all this comedy and situations on top of it. I’ve never liked like, slapstick comedy, but just comedy that’s a little bit more sophisticated – not that Monkey Island is sophisticated.

Do you find that it’s quite easy to write comedy for videogames, because it’s one of the few mediums where it’s quite hard to do for many others?

No, it’s actually really hard, because if you do comedy in a movie or a TV show or something then you have total control over timing – and comedy is all about timing – and you have no control over timing in a game because you’re giving timing up to the player; they’re now the ones who get to decide timing. Humour is just very hard to do, if you take people who are quite funny in TV and movies, they’re used to having better control of the timing and they find it very frustrating that the players now have control of that.

How much on an ongoing process is writing in your games? Do you write the script at the beginning and that’s that, or do you have to keep changing things on the fly as development demands?

I tend to write late. I wait until we get the structure of the game laid down, and I know the story all in my head, or I’ve maybe written a two or three page overview of the story, but it’s not until maybe halfway through the game that I’ll actually start writing dialogue. I want to have time to feel the game before I start writing dialogue. There’s stuff in The Cave I rewrote like three times, and he just wasn’t working; he was talking too much, and we had to say we didn’t want to listen to the Cave this much, so I rewrote it so he talks about important things, not non-stop throughout the entire game. Then I wrote more in, because I never liked that fact that he originally never addressed the player, it was like he was just thinking inside of his head, and that wasn’t really working either, and so I wrote it again where he continually address the player, and that just made it all come together. It felt a lot more personal with the dialogue talking to the player.

How does the writing process change in comparison to your earlier titles like Deathspank and Monkey Island?

The writing in Monkey Island was very free-form; we were programming the game – because we really didn’t have writers – and it was just myself and Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer and they were just programmers on the game, so the writing was a lot more free-forming. We’d program something and then we’d write a little bit, program something then write a little bit, where Deathspank for example, that was something where I really had to think about the writing because a lot of it was also done by a guy somewhere else. He lived halfway across the country, and so I had to really, really structure everything down and then send him off to write the actual dialogue. With The Cave, I just kind of waited until halfway through the project before I started writing, so I think it changes and it’s kind of free-form.

I’ve heard that there were originally up to 20 or 30 different concepts for playable characters, how did you manage to whittle it down to the final seven?

I’ve heard that there were originally up to 20 or 30 different concepts for playable characters, how did you manage to whittle it down to the final seven?

It was pretty easy until I got down to about ten. It was really easy to scratch people off, you know, a clown – who really wants to play a clown? Scratch him off. When we got to around ten, then it became a lot harder, and we actually started designing the game assuming we had the ten – we knew we were going to cut – but we really just wanted to see which of the characters started to get more interesting, what areas could we come up with, and then we started cutting them as we got those down. There was concept art for a Mobster character, he was eventually cut because he didn’t end up being that interesting.

If The Cave were actually real, would it be something you’d explore yourself?

Oh, we’re all going into The Cave at one point in our lives. That’s why we’re here, isn’t it?

The Cave is out now for the PC, XBLA, PSN and Wii U.

Last five articles by Edward

- Best of 2015: Journey's End: A New Beginning

- Journey's End: A New Beginning

- You Can't Choose Your Happy Ending

- Okay, Let's Fix Comedy In Games - The V-Effekt

- Time Keeps On Smashing Away

This was news to me, didn’t even realise this was in progress, let alone released! Great piece, Ed. The game sounds right up my street too, ticking a few major boxes: unforced multiplayer, replayability, something a little different. Question is, are you glad you met your hero?? =D

Nice one, Ed.

Looks better than I thought it would. It will go on my ‘good intentions but never likely purchase’ list.