A Happy Ending

by Adam

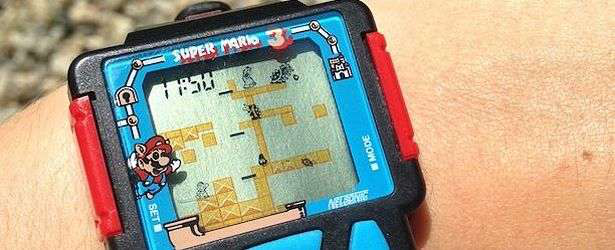

It’s been twelve hours since you pressed ‘New Game’ and the credits are rolling, it’s all over. Your quest to save the world has been a success, you are the hero of the land and everyone is safe, all thanks to you. The credits come to an end, all characters are fictitious and any likenesses to persons living or dead are entirely coincidental, now go and play something else. Apart from the ‘twelve hours’ part, the above was very much the mainstay of video games as a kid. We’d happily sink whatever time we had into the adventures of a space marine, man in loin cloth or freak of evolution animal without so much of a bat of an eyelid once it was all over. Most games didn’t bother with a plot, just a simple system of progression where things just got a little tougher for you, and the music raised its tempo just enough to make you think that it was somehow more important for you to reach the end of the level.

These days games have to have a carefully laid out plot, with clear indications about who you are, where you’re going and why it’s so important that you get there. Everything is so plainly telegraphed that the endings are often a disappointment, you knew that all of this was going to happen and you will only be thankful if it’s you that’s allowed to do it, rather than being forced to watch as a cutscene takes that pleasure from you.

Enter, the twist.

No, not the popular jive dance from ‘mid-nineteen fifties no-one-gives-a-crap’, just that tiny little thing you didn’t see coming, which makes the ending that little bit more eventful, throwing you bolt upright from your casual slouch and switching your brain into overdrive twelve hours later than the game probably should have. It’s perhaps become the norm now to even expect the twist, having you second guess every little detail in the characters and the plot along the way, which the writers have designed to convince themselves that they’re the next J.J Abrams. Sometimes that doesn’t always pan out quite like they’d hope and, come the end of the game, you’re just left standing there, with more questions than answers and less satisfaction than you expected for the price you paid in cash, time and effort.

With sequels being the primary requirement to selling a great game these days, this is made even worse when the twist comes, smacking you in the face as hard as it likes and then laughing loudly as it runs off into the sunset, knowing that the sun doesn’t rise again for another eighteen months. Of course, it’s never just eighteen months, so two years later when you’re hoping to get those answers, imagine the disappointment you feel when the writing staff have been shifted to a different project and a new team bought in. A new team with different ideas that conflict slightly with the old ones, meaning that those answers you’ve been waiting for are either going to be tied up so fast you’ll blink and miss it or otherwise get left by the wayside altogether.

It’s rare these days that we can stick in a game and play the whole thing through from start to finish, moving on into the multiplayer with a feeling of satisfaction that you haven’t had in quite a while. There are few developers these days that have the luxury of being able to do that, ignoring the cries of the publishers to leave a few bits out so that it can be sold as DLC later on down the line or kept back for a stopgap sequel in the next primary gifting period. With multiplayer proving the most popular feature in a game these days, maybe it’s just not as big a concern as I believe it to be, with the hungry horde of millions all too happy to forsake advancement in the campaign for XP gains in the multiplayer component. But sometimes, it’s just too jarring for as passionate a gamer as myself to ignore.

Take Halo 2 for example. The anticipation was always going to outstrip the experience, but few could have foreseen the burn Bungie had waiting for them at the end of its heavily criticised, short campaign. Coming off the back of the neatly contained Halo: Combat Evolved, it’s probable that the developers never foresaw the need to lay the foundations of the trilogy it would go onto become, and so all of that work had to occur in Halo 2. This left the game becoming entirely bogged down in politics and backstory you just didn’t care about and, just when the tempo was reaching something recognisable as satisfactory, the game ground to an absolute halt. The final scene with Master Chief telling Hood he had returned to Earth to finish the fight, followed by a rousing chorus of the game’s main theme was exactly the kind of upright, trigger-finger clenching sitting we had spent this game waiting for and the credits which immediately followed Chief’s declaration couldn’t have been a bigger slap in the face.

It wasn’t the ending we were expecting but, then again, what would have been? Had the game continued and Master Chief dived down to the planet surface, ready for one last fire-fight, who would he have fought that would have quenched our bloodlust? To have just entered into one last battle with the Covenant would have just been a repetition of the game’s opening, with still no clear or identifiable way of closing out the game without a complete routing of the Covenant from Earth. Perhaps Bungie could have extended that fight long enough for Gravemind to be seen crashing the High Charity through Earth’s atmosphere, giving the player the satisfaction of knowing they had won one fight, but started another, ready for Halo 3.

It wasn’t the ending we were expecting but, then again, what would have been? Had the game continued and Master Chief dived down to the planet surface, ready for one last fire-fight, who would he have fought that would have quenched our bloodlust? To have just entered into one last battle with the Covenant would have just been a repetition of the game’s opening, with still no clear or identifiable way of closing out the game without a complete routing of the Covenant from Earth. Perhaps Bungie could have extended that fight long enough for Gravemind to be seen crashing the High Charity through Earth’s atmosphere, giving the player the satisfaction of knowing they had won one fight, but started another, ready for Halo 3.

Where Halo 2 failed, Halo 3, of course, prospered so ultimately it’s something we’re all too happy to forget and forgive Bungie for. With the might and money of Microsoft looking out for you though, Bungie knew that they could take such a risk with Halo in a way that very few games are willing to. Were it that we played one of the Grand Theft Auto games and saw its story die of a sudden heart attack, just as one of its many plot twists takes centre stage, we’d all probably rally together in a crusade on Rockstar’s offices that would make them wonder if Celtic and Rangers were playing that day. Sure, if they still left us with the keys to the city, some of us would be content enough to just send along an angry note with our overly enthusiastic friends, carrying on jacking cars, running over the owners and then launching the vehicles into the sea just for funsies. We’re fickle like that.

Other times, we’re just too loyal to say anything bad about our beloved games and, like a religious nut who denies the existence of the Easter bunny, we just won’t stand for that kind of talk. Half-Life is probably the definitive game of my life. It changed the way I viewed narrative in a game and taught me more about solving a problem from its first person perspective than any wannabe pirates or American tourists ever could. The game is a masterpiece in my eyes with but one flaw…

Half-Life’s ending was just bizarre. Having spent the best part of the game looking for a way to escape Black Mesa, the rest of the game, spent avoiding containment by the military and somehow fighting off the Alien invasion while doing so, seemed perfectly reasonable. The decision to travel to Xen in order to stop the Resonance Cascade with little hope of ever coming back feels a little out of place, for sure but, as the hero of the story, it felt like a sacrifice that just had to be made. At the point where you reach the Nihilanth, you’re starting to wonder if they’re not just making this all up now, trying to give you one last funny looking bug-eye to stand victorious on, only for that moment of glory to be stolen from you and switched with a bleary eyed confrontation with the G-Man. To be told that this whole thing has proven to be little more than a violent episode of The Apprentice for some kind of shadowy Alan Sugar overlord isn’t so much disappointing as it is disorientating. You don’t quite have the time to ask ‘WTF’ nor the ability to process those three simple letters in the first place. It’s a better ending than most but, much like Halo 2, it’s only truly alleviated of its bizarre ending by its successors efforts to help explain it.

But what makes for a good ending? Can we ever be happy, knowing that we’ve exacted revenge upon the figure that saw us take to arms in the first level? Do we need to feel the consequences of our actions and, if we do, do we then accept that our choices have validated our feelings towards our chosen conclusion? Or do we just need to be shocked and awed by the developers so much that we’re made to forget any questions we may have.

I recently completed Red Dead Redemption, after a solid year of drifting in and out of its campaign. I never did sink my way into the story quite as comfortably as others, feeling as frustrated as Marston that I was tasked with trivial hand holding along the way that ultimately dragged me clean out of caring for the fate of his family at all. Having logged on to the Rockstar Social Club a few nights before making that one final push, I was told that I had but ten missions left to complete, yet I knew that the very first step on the path to the credits was the final chapter in Marston’s tale of revenge.

I recently completed Red Dead Redemption, after a solid year of drifting in and out of its campaign. I never did sink my way into the story quite as comfortably as others, feeling as frustrated as Marston that I was tasked with trivial hand holding along the way that ultimately dragged me clean out of caring for the fate of his family at all. Having logged on to the Rockstar Social Club a few nights before making that one final push, I was told that I had but ten missions left to complete, yet I knew that the very first step on the path to the credits was the final chapter in Marston’s tale of revenge.

I didn’t know that from a ‘spoilers’ point of view either, it just felt natural that Rockstar were finally going to give me the carrot they’d been dangling in front of me the entire duration of the game. But the carrot isn’t the end. Once you’ve finished eating that carrot, you pick up the stick that the lure was tied to and you scratch your head with it, wondering where you go from here. Like a Schizophrenic Alzheimer’s patient who has pissed themselves in somebody else’s house, you then walk around the final nine missions of the game with the odd sensation that something’s not quite right, and fear the game’s reassurances that trouble has finally left paradise as actually being something rather more sinister.

It’s yet another entirely unique ending to a video game that winds you down from your life of high-strung adventure and on-the-run and gun gameplay, into a sensible form of retirement that no other game has ever provided. For the first time in years, the game left me feeling satisfied when the end credits rolled in a way I just wasn’t expecting. I’d spent the entirity of RDR so disconnected from the story that I was only ever finding myself enjoying the game in its absence, riding the dusty trails with a poor innocent shopkeeper lassoed behind me, headed straight for the cliff’s edge, ready to leap from my horse at the last possible second and letting Binky and Marv go a tumblin’. Stopping Dutch became a fairly low priority in the game, sitting somewhere just above saving the family I’d never met, but considerably lower than waiting at the side of a rail track in the hope a bunny would hop his way into a train’s path for my own amusement. It was only in those last few moments that I finally felt a solid connection with John Marston and it amazed me that a game that had otherwise bored me to tears had managed to do that. While the ending itself was far from a happy one, I felt happy that I’d been a part of it.

Whatever happens with video games in the next few years is anyone’s guess. They say we’ve seen just about every story there is to see in one medium or another, but if a game like RDR is able to throw up those moments of purified surprise, without needing to promise a sequel or beg you to stick around for the multiplayer so that you feel like you’re getting your monies worth, maybe we haven’t seen everything yet. With so much pressure on the developers to turn a profit and garner enough support to provide them with the opportunity to invite you all back eighteen months down the line, maybe we’re doomed to suffer the promises of a happy ending more than the happy ending itself. Perhaps it’s less about the destination though, and my real thoughts should be on the journey, happy in the promise of cake and content enough in that to ignore that there is no cake at the end of the tunnel?

What are you mad? Screw that, I’ll have my cake and I’ll eat it thank you very much.

Last five articles by Adam

- Party Pooper

- Battlefield 3 - Review

- Red Orchestra 2: Heroes of Stalingrad - Review

- Burnout CRASH! - Review

- Dead Island - Review

I thought I didn’t care much about stories and endings but EDF:IA’s non-ending irritated me beyond tablets.

That said, Bomb Jack didn’t need a story.

Very thought provoking Adam. One of the best article’s I’ve read in a while I think. Good stuff.

I agree to disagree on the Half Life ending. I feel that it was something of a relief to be left with no control and practically no choice about what was going to happen to me. Going to the Xen world did seem a little odd, but made sense aswell. I don’t think Valve were brave enough not to include some sort of alien world. All the shooters were doing it back then!

Too pull the same shit at the end of Half Life 2 though in relation to the actual ending was a pain. Glad it wasn’t replicated for episodes 1 and 2

I love this article

I spent ages trying to think of the worst ending to a game I could possibly think of, and it has to be Red Steel. It was a bit of a crap experience as it was, but you reached the end of the game, did a sword fight against the guy you’ve been trying to kill the entire time, then had a sword fight with your mentor because he was trying to kill the guy you’d been trying to kill the entire time, then after it changed to about six still images with voiceover. My mentor literally said something along the lines of “It wasn’t the poison killing my daughter, but our own intolerance and greed”, and then you saved the day and the credits rolled. It was so bad I was about to throw the disc out the window until I remembered it wasn’t my copy.

So that’s the worst modern ending I’ve witnessed, in any case.